October 1944

The 100th Infantry Division was activated in November 1942 in Fort Jackson, South Carolina, went through specialized training in the Cumberland Mountains of Tennessee and continued to Fort Bragg, North Carolina through most of 1944.

The Division was well trained and prepared to play a key role in the late stage of the war in Europe. In October, they were called to duty and boarded trains for Camp Kilmer New Jersey. After final supplies and staging were arranged, they were ferried across the Hudson River to the piers on the west side of lower Manhattan to board ships and embark on a trip across the Atlantic Ocean, to the Mediterranean Sea, and to the port of Marseille, France.

Tom was 28 years old, married for two years with one daughter, Kathy, and his wife, Kate, pregnant with their second child. He was older than most of his troops, had completed officer training and reached the rank of Captain in the 398th Regiment, Company E. Writing letters to Kate was a habit he practiced whenever possible, and fortunately Kate saved all of his correspondence while overseas.

Below is Tom’s account of his voyage that October.

…“You know I’ve been wondering just how much you have learned about the movements of the Division since we’ve been overseas. There is no censorship about such matters now, so in case you are interested I’ll tell you a few things in each letter so you can catch up on our history.

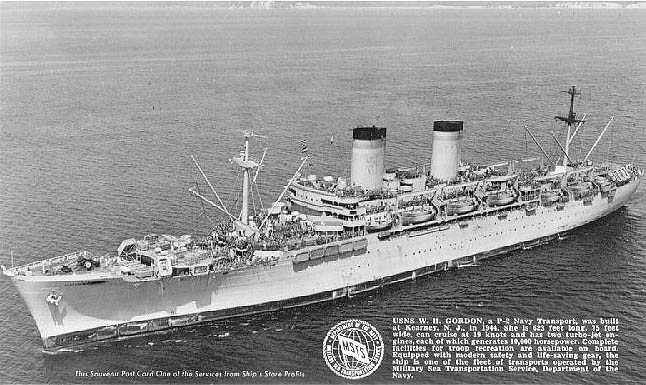

We left the States Oct.6th and landed at Marseille October 22nd. We came over in convoy, the 100th – 103rd-and 12th Armored Division. Also included were a baby aircraft carrier (British) headed for Oran and some refrigerator ships. The 398th and 375th Field Artillery and a few other minor units were together on one of the ships, the General W.H. Gordon. It was a 10,000-ton naval transport, manned by the Coast Guard. The only larger ship was the “George Washington” which was the reconverted “Conte Grande” of the Italian line. Our ship was the fastest of the convoy (except for the escort) being capable of doing over 20 knots under full steam. This was her second voyage. She had helped bring the 44th Division over about a month previously on her maiden voyage. We were convoyed by one destroyer and three destroyer escorts. The first few days of the voyage were beautiful and calm, but about the fifth day out we ran into a blow. It was a full scale North Atlantic gale. We tossed about for three days until it finally blew itself out! There were seasick guys everywhere but I didn’t miss a meal. (We were only fed twice a day, breakfast and supper). It cleared up beautifully before we sighted land. Our first glimpse of terra firma was the African coast; we sailed up it and into the Mediterranean. It was at dusk that we sighted Gibraltar- a really breath-taking sight. We slid by it and awoke the next morning to find ourselves in the blue Mediterranean waters. We again stuck to the African coast for a while until nearly opposite Marseille, when we swung north. We were now entering the airplane danger zone because Italian based German planes were attacking Shipping in that part of the Mediterranean. But as it turned out we had little to fear then, because a hell of a storm sprung up and no planes could fly, and some storm it was!, even worse than the Atlantic version. The same guys were violently ill all over again. But the wind had blown good as well as evil and we arrived in port unscathed.

There are lots of details that I could add to this short account, but the biggest one was the fact that I was beginning to learn how much I could miss a person, and how miserable and lonely and frustrated a fellow could be away from the one he loved with only a 50-50 chance of getting back.”…

Tom’s letters described some sense of his daily life and would spotlight characters and vignettes the he thought Kate might find amusing or interesting. This is an excerpt of a letter he wrote to her while he was actually on the ship and mailed after arrival in France.

“On the Briny Deep

My Darling,

She’s really beginning to toss and pitch tonight. More and more of the men are becoming seasick but there’s no help for that. I’m still holding out. As a matter of fact I feel fine and have a wonderful appetite. I must have some Irish sailors among my forebears.

Life on board is becoming rather monotonous, although it is not too unpleasant. There’s always someone to shoot the breeze with. Rendell and I chew the rag quite a bit. He’s fine and so is Warren.

John Henry (A senior officer) came through with another stunner today. We have to wear ties to all meals, but otherwise it is not necessary. Someone asked him when a tie had to be worn and he replied, “For meals it is compulsitory, but at other times it is optionary.” How he does it, I’ll never know. It must be a gift.”

October 1944

A few days later, Tom continued his account of the 100th Division’s arrival in France in October of 1944 in a letter to Kate.

…”Would you like to hear some more about the 100th’s hegira? Here goes-

We pulled into the port of Marseille October 22nd. The convoy was fairly large and only a few ships could be unloaded at one time because of the damage which had been done to the docks by our air corps before the 7th Army invaded southern France, or by the Germans before they withdrew. Traditionally, the ships were unloaded in order of their Commander’s rank. Fortunately our Captain was third or fourth ranking man, so we didn’t have too long to wait before our turn came. We marched down the gangplank with all our belongings on our backs in enormous full field packs weighing about 60 pounds each. We filed between a throng of GI onlookers on either side of us who hooted at us derisively making insulting remarks about us individually and collectively and telling us that our clean uniform and equipment would be soon dirty and torn. We did our best to ignore them, formed up and marched off. We were heading for concentration areas outside the city where we were to be processed. We had no idea how far they were.

Arrival in Marseille France

Humphrey Bogart – Acting as if we were in Marseille

(Passage to Marseille – 1944)

Imagine our consternation when we learned that our camp was fifteen miles from the dock area, ——— and us with at least 60 pounds on our backs and two weeks of inactivity and seasickness (in most cases) behind us! We had eaten no lunch and all we had with us was one K-ration for supper when we set out at about 3pm — what a march that was! Packs cut into backs and shoulders – feet became sore and blistered in new shoes; hungry stomachs made us slightly nauseous; stiff muscles ached with fatigue; — but not a man in the company dropped out.

We were just leaving the city and dusk was settling when suddenly all the searchlight batteries in the city lit up the sky and the ack-ack guns started spitting. A lone German bomber had slipped over from Italy to raid the harbor area. It was our first taste of that thrilling but nauseating reaction to combat. Of course, we were in no danger at the time, but we didn’t know that and everyone felt sure that we were going to be bombed and strafed. We suddenly realized that there was a war going on.

Close to midnight, we finally reached our campsite, a bare open field between a railroad embankment and a highway. It had begun to drizzle. We were all completely exhausted but we had to arrange to sleep somehow. Warren and I got together. (He and Sam Passero had gone ahead earlier by motor as a quartering party and had led us into our area from about a mile away.)

I was too weary to worry about pitching a tent, so we just laid a shelter-half on the ground, put a couple of blankets on it, covered it with another shelter-half which we pegged down and crawled between them and promptly went to sleep.

Next morning we woke up (but of course) to find the field a mass of sticky brown French mud. We ate some C ration for breakfast (it tasted like an 8 course dinner at the Waldorf) and set about pitching our tents in an orderly arrangement. We spent a good amount of time hunting equipment we had mislaid in the dark.

Then the opinions and rumors started to fly. We were going to be held here for further training; — we were going to the front immediately; — we were going to be used as occupation troops; — we were going to be split up into combat teams and used separately in different areas; — and a score or more of other things.

But nothing sensational happened for a while. We just went about the business of getting our heavy equipment, unpacking it, cleaning it up, getting new vehicles, –and living in the mud and almost continual rain. The boys aptly named the place “Pneumonia Gulch”.

We began to trade with the natives – cigarettes, candy, soap, C ration, chocolate and everything else we could lay our hands on for fourth rate wine. We also walked to neighboring towns to see the sights, parlay our high school French and wander in and out of the wine-shops. Some of the boys immediately discovered the establishment, which they seem able to find in even the most out of the way places——-the local brothel. So we had the problem of venereal disease to contend with again, and prophylactic stations needed to be opened.

But one morning after we had been there for about a week, the electrifying news came: we were going to move up to the front! So the next phase of our journey began – this time in freight cars, the famous forty and eights of the French railroads. However, that deserves a chapter of its own.”